From Bone Whistles to Billion Streams: The Beautiful, Messy Story of 'World Music'

Discover how 'world music' evolved from 40,000-year-old bone flutes to billion-streamed K-pop hits. Explore the contested origins, key artists, and cultural debates shaping global sounds from ancient.

Bone flutes carved 40,000 years ago and a K-pop single streamed a billion times share something surprising: both sit under the loose banner now called “world music.” Coined during a London pub marketing huddle in 1987, the label was meant to help record-store clerks file everything from Afrobeat to gamelan on one shelf. The sounds themselves, of course, began with humanity’s earliest rhythms and kept evolving through trade routes, colonization, vinyl crates, and now the digital cloud.

Understanding how a catch-all category grew from prehistoric caves to streaming playlists gives every note more color. In the pages ahead you’ll trace a timeline from bone whistles to Billboard charts, meet the artists who carried traditions across oceans, and pick up ethical listening tips for the Spotify era. By the end, you’ll know exactly what “world music” means—and why its history matters each time you press play. First up, let’s pin down the term itself.

Defining “World Music”: Origins of a Contested Term

Ask ten listeners to define world music and you’ll get eleven answers. The phrase itself didn’t surface on album jackets until the late-1980s, yet its academic seedlings sprouted two decades earlier. In plain terms, “world music” is an industry shortcut for recordings that sit outside dominant Anglo-American pop and classical traditions. That umbrella can stretch from Malian kora epics to Japanese shakuhachi meditation, but it does not automatically include every non-English track, nor does it replace more precise genre names such as Afrobeat, tango, or gamelan.

People Also Ask quick hits: What is the origin of world music? It emerged as a commercial category in 1987 when British and U.S. labels agreed on a shared shelf label. Who started world music? No single artist; the term was championed by ethnomusicologist Robert Brown in the 1960s and later formalized by record-industry marketers.

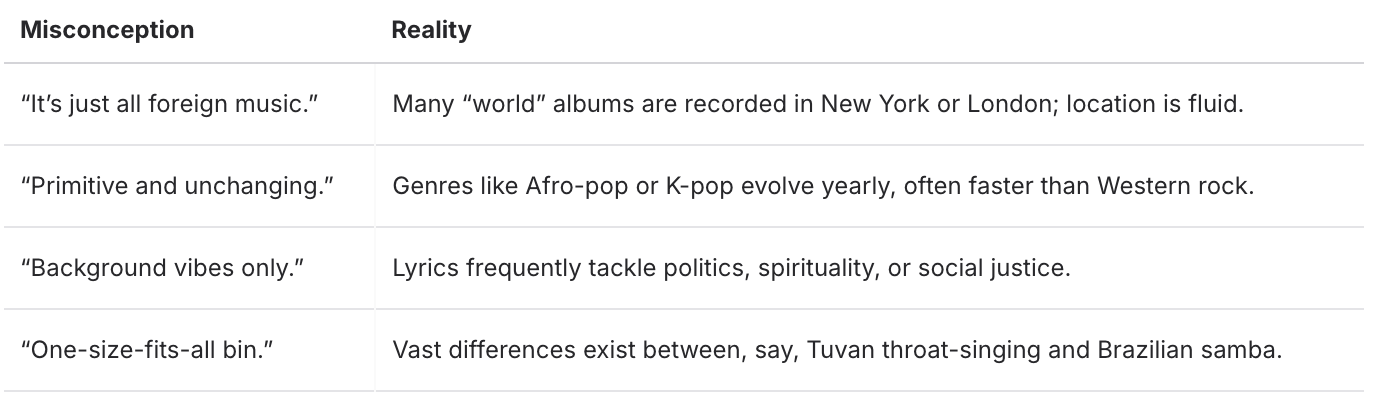

Common myths still muddy the water:

The next three snapshots show how the label took shape—and why some musicians now reject it outright.