Classical Music Era: What It Is, Key Composers & Hallmarks

Discover how the 1750–1820 Classical Era defined Western art music through Haydn, Mozart & early Beethoven—its timeless balance still shapes today's symphonies, exams, and film scores.

The Classical Era in Western art music runs roughly from 1750 to 1820, sandwiched neatly between the ornate Baroque and the emotion-charged Romantic periods. Think of music that prizes balance, singable tunes, clean textures and well-shaped structures – the symphony, sonata, string quartet and concerto all took on the shapes we still recognise today. Haydn, Mozart and early Beethoven were its headline architects, but hundreds of composers helped refine a style where clarity always trumped complexity.

Understanding this seventy-year slice of history matters because it underpins almost everything that followed: nineteenth-century Romanticism, film scores, even the pieces pupils tackle for grade exams. In the pages ahead you’ll gain a timeline to keep the eras straight, decode the Classical sound, meet its star composers, tour the genres they perfected and discover how concerts and instruments of the day really felt. By the end, you’ll hear familiar works with freshly tuned ears.

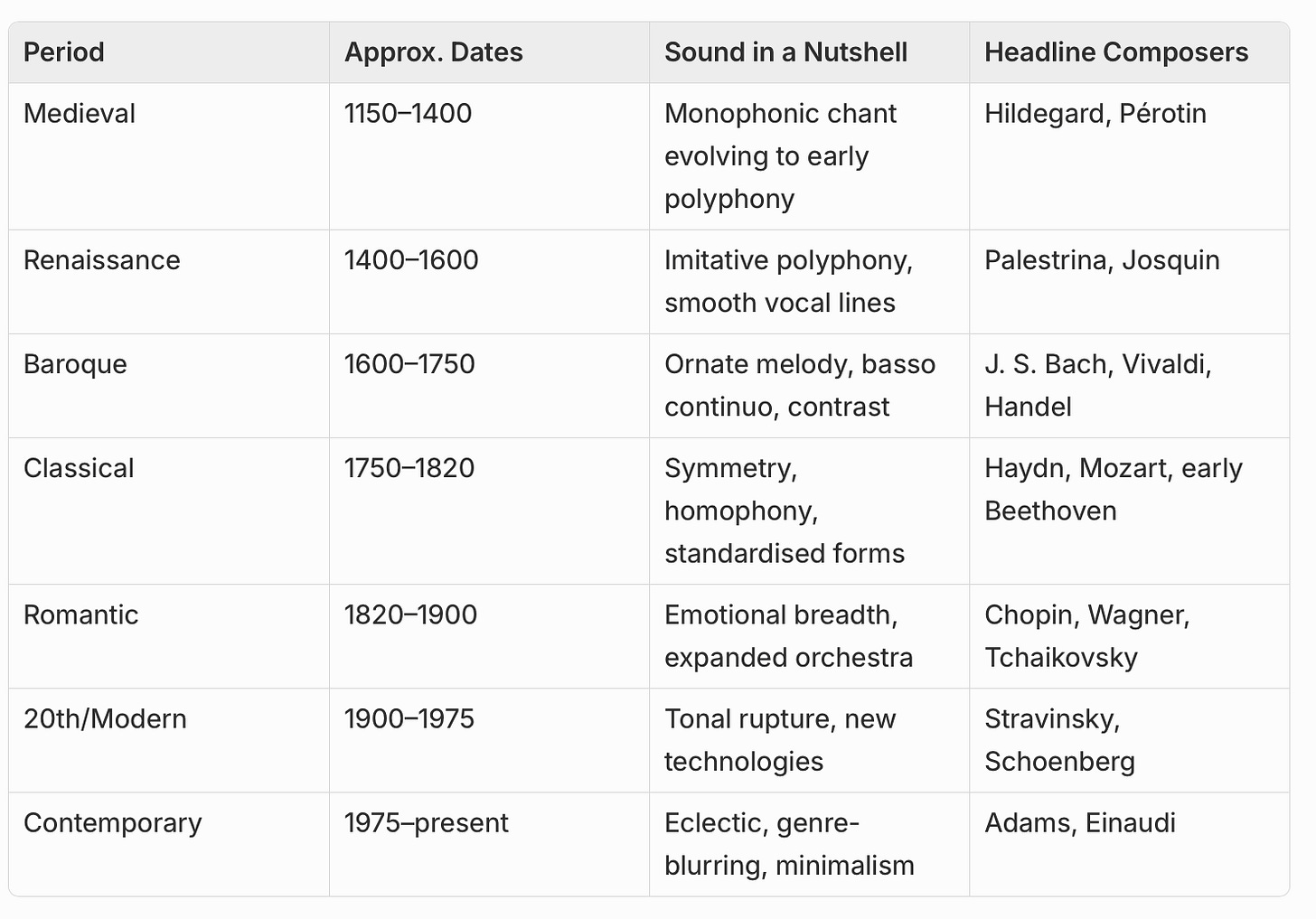

Where the Classical Era Fits in the Grand Timeline of Western Music

Western art music unfolds like a relay race, each period handing ideas to the next. The baton starts in the Medieval monasteries, gathers polyphonic momentum in the Renaissance, blossoms into Baroque ornamentation, straightens into Classical balance, swells with Romantic passion, fragments in the 20th-century search for new sounds and keeps morphing today.

Because the umbrella term “classical music” is often used for everything not on the pop charts, it’s easy to forget that the capital-C Classical era covers barely seventy years. Yet its lean, transparent style became the reference point against which later composers rebelled or built.

The years 1750–1820 also mirror seismic shifts outside the concert hall. Enlightenment philosophers championed reason and individual rights; revolutions in America and France challenged hereditary power; the early Industrial Revolution created a growing middle class hungry for culture. These currents reshaped who wrote music, who paid for it and who could hear it.

Visual Periods Timeline

Baroque’s exuberant counterpoint gives way to Classical order, which in turn seeds Romantic expressiveness—a neat stylistic sandwich.